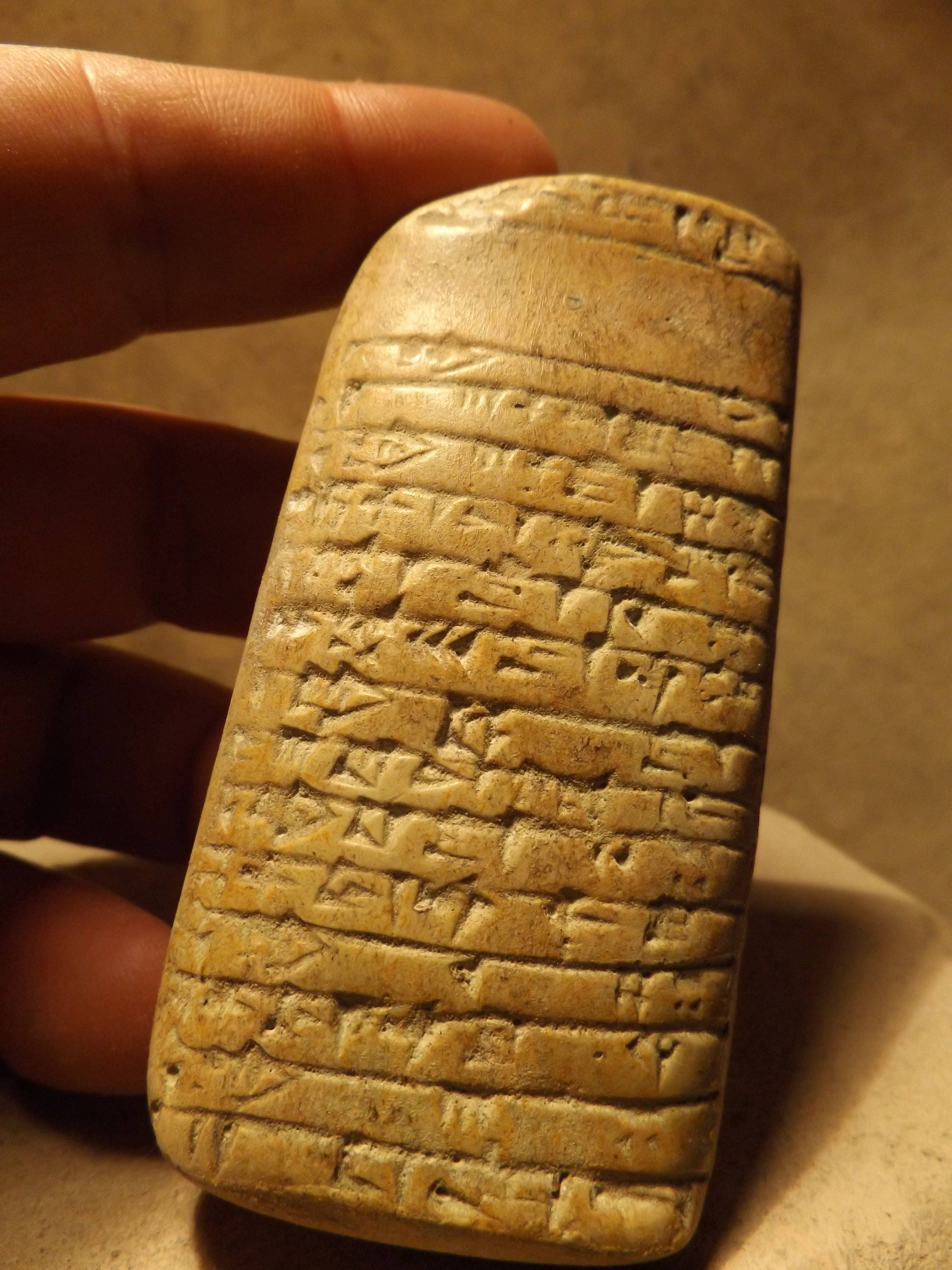

From Klaus WagensonnerĪfter Ura, students studied more advanced lists, including metrological lists and mathematical tables, but also syllabaries ( su ch as Ea and Diri) and word lists whose entries ar e arranged according to their initial signs ( f or example, Izi, Kagal, and Nigga). 4: A copy of the thematic list Ura dealing with wooden objects. At this stage, he was still far from being as accomplished as the scribe of a small tablet inscribed in an astonishingly tiny script, which contains almost two hundred entries belonging to the same thematic list it dates a few centuries later ( Figu r e 4 ).įig. On the “Type II” tablet, for instance, the student copied lines from Ura concerning domestic animals. In copying e xtracts, students usually just sampled t he many entries of the list. During the early second mill e nni um, these designations were still almost exclusively Sumerian. This was achieved by copying an important thematic list, a forerunner of what would e v e ntually become a compendium spanning thousands of entries that according to its first entry was referred to as Ura, “loan.” This long list contained designations of tr ee s and wooden objects, other raw materials, animals, geographic entities, and also food items.

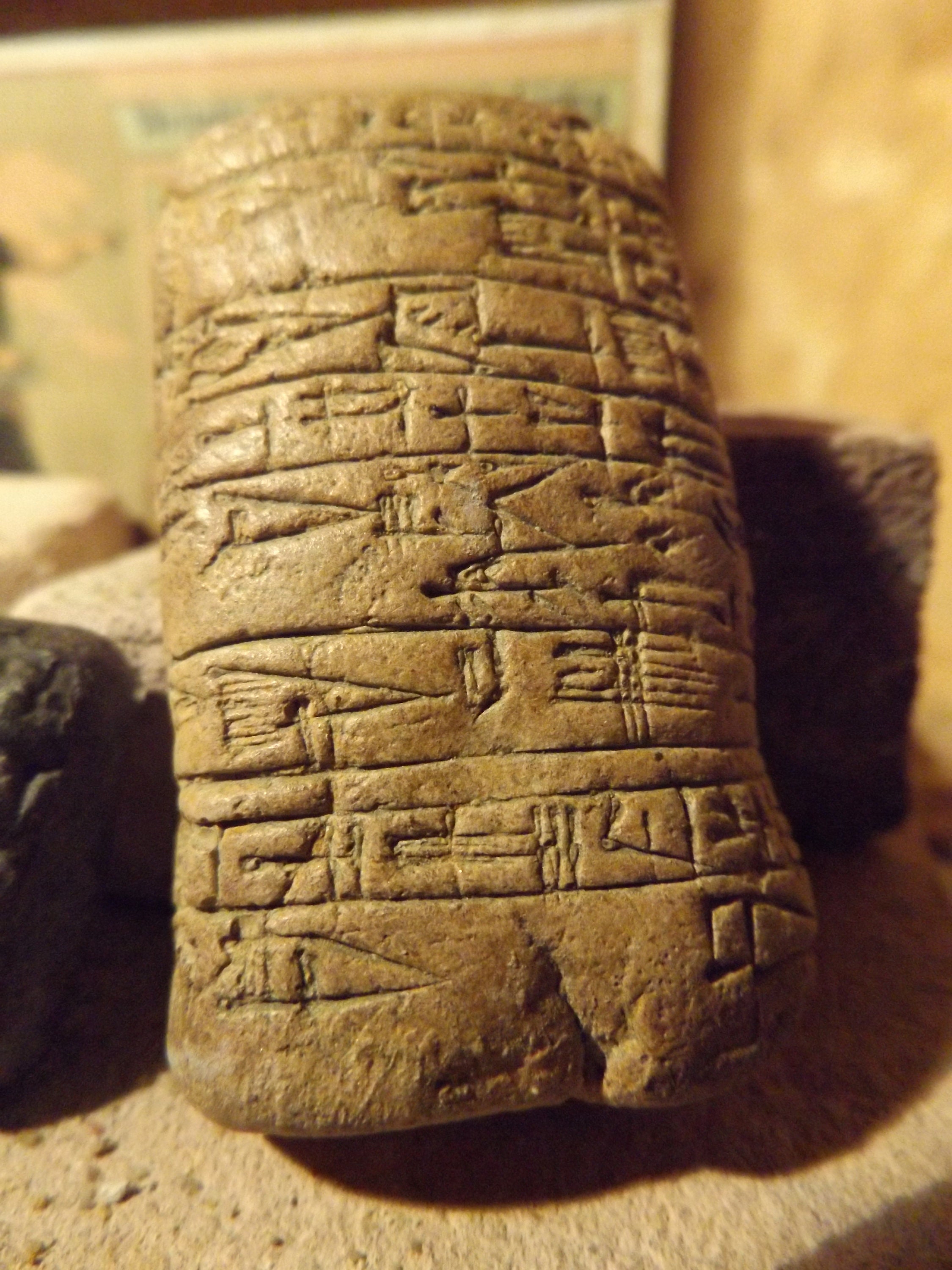

In t he ne xt phase of their studies, the “s on s of the tablet house” (Sumerian: d u m u e 2 – d u b – b a – a ) had to expand t he ir vocabulary. 3: Practicing syllables: Syllabary Alphabet A (on left) and TU-TA-TI (on right). S imilar exercises can still be found in the late first mill e nnium BC. To gain some routine, the student impressed his stylus over and over again into the clay ( Figu r e 1 ), producing the horizontal, v e rtical, and oblique wedges of which cu ne iform characters were comprised. A famous li ne from a lit e rary work points out, “T he be ginning of t he scribal art is the single wedge”. The ne xt challenge was to use a reed stylus to form intelligible signs on the c lay. The first step was to cover the basics: transforming a lump of moist clay into a tablet. The apprentice start e d his train ing as a child, probably at the age of five or six years. “ Go! Knead your tablet! Mak e it! Write it! Finish your tablet!”-these brief instructions in a b ilingual vocabu lary offer a short glimpse into the daily tasks of a scribe. In this essay excerpt, author and scholar Klaus Wagensonner gives us an intimate view into how the ancient scribes, the creators of Mesopotamia’s vast written record, learned their craft.

Mesopotamia has left us with a massive legacy of information about this ancient people’s literature, beliefs, government, diplomacy, conflicts, science, economy, trade, family life, and even their personal relationships, food and cooking. Editor’s Note: The fascinating details of ancient civilization come alive most lucently through written records, and it was in ancient Mesopotamia when writing first advanced to the point where the human record really began to tell a story about the past.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)